|

“Recently more and more enterprises organised abroad by American firms have arranged their corporate structures aided by artificial arrangements between parent and subsidiary regarding intercompany pricing, the transfer of patent licensing rights, the shifting of management fees, and similar practices [...] in order to reduce sharply or eliminate completely their tax liabilities both at home and abroad.”

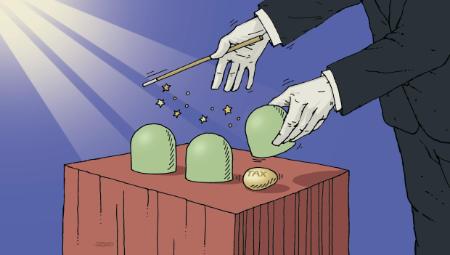

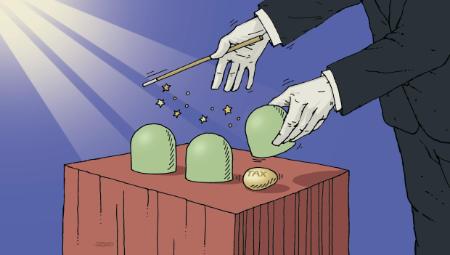

These words were not uttered recently in reaction to the many stories of tax avoidance currently in the media. Rather, they are the words of President Kennedy in a statement made in 1961. Yet they have an uncanny relevance today as the list of global tax controversies lengthens, often concerning household names of the new transparent, “flat-management” global economy. The newspapers are full of stories, with Bloomberg’s “The Great Corporate Tax Dodge”, the New York Times’ “But Nobody Pays That”, The Times’ “Secrets of Tax Avoiders” and the Guardian’s “Tax Gap” as only some examples of the increased media attention to corporations’ tax affairs. Civil society and NGOs have been even more vocal, sometimes addressing very complex tax issues in a simplistic manner and pointing fingers at the arm’s length principle (based on which different entities with a multinational enterprise, or MNE group, are required to transact as if they were independent, for tax purposes) as the cause of all these problems.

This increased media attention and the inherent challenge of dealing comprehensively with such a complex subject has encouraged the perception that the rules for the taxation of cross-border activities are regularly broken and that taxes are paid only by the naive. MNEs stand accused of dodging taxes all around the world and in particular in developing countries, where tax revenue is critical to foster long-term development. Little wonder demonstrations by angry taxpayers have taken place in several global locations recently.

Of course, businesses have a responsibility towards their shareholders to maximise their profits, which means legally reducing the taxes their companies pay. They consider most of the accusations to be unjustified and point out that their multinationals are subject to double taxation on their profits from cross-border activities, with speedy agreements among governments on which country should tax what as utopia.

The debate over base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) has reached the highest political level and has become an issue on the agenda of several OECD and non-OECD countries. Governments are responsible for designing their tax systems. The G20 leaders’ meeting in Los Cabos on 18-19 June 2012 explicitly referred to “the need to prevent base erosion and profit shifting” in their final declaration. G20 finance ministers, triggered by a joint statement of United Kingdom Chancellor George Osborne and German Finance Minister Wolfgang Shaüble, have asked the OECD to report on this issue by their meeting in February 2013. Such a concern was also voiced by US President Barack Obama in his Framework for Business Tax Reform, where it is stated that “the empirical evidence suggests that income-shifting behaviour by multinational corporations is a significant concern that should be addressed through tax reform”.

The OECD is acting on this call. After all, helping to develop rules that support the efficient operation of global markets is one of our key objectives . This involves providing a policy framework that achieves a fair allocation of taxing rights between countries. The arm’s length principle and the elimination of double taxation are essential elements of that framework, but so is the elimination of inappropriate double nontaxation, whether that arises from borderline strategies put in place by aggressive taxpayers or from tax policies introduced by national governments.

It is easier said than done. The first step was to carry out an in-depth analysis of BEPS issues to identify what the problems are and the different factors that have determined them. For years the OECD has promoted dialogue and co-operation between governments on tax matters. There is the Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital which forms the basis for negotiation of the more than 3,000 existing bilateral tax treaties in the world. There are the Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations, which embody the international standard to allocate profits among different parts of an MNE group. Several studies have been carried out on aggressive tax planning to help governments respond more quickly to tax risks. The Forum on Harmful Tax Practices has built support for fair competition and minimised tax-induced distortions, with more than 40 regimes identified over time as potentially harmful, all of which have been abolished or modified. And, of course, the work on tax policy and statistics, which has dealt with the effects of taxation on foreign direct investment and how to implement sensible corporate tax reforms.

The OECD published Addressing Base Erosion and Profit Shifting in February 2013. The report analyses the root causes of BEPS and identifies six key pressure areas: (1) hybrids and mismatches which generate arbitrage opportunities; (2) the residence-source tax balance, in the context in particular of the digital economy; (3) intragroup financing, with companies in high-tax countries being loaded with debt; (4) transfer pricing issues, such as the treatment of group synergies, location savings; (5) the effectiveness of anti-avoidance rules, which are often watered down because of heavy lobbying and competitive pressure; (6) the existence of preferential regimes. The report was discussed at the Moscow G20 meeting of finance ministers who expressed strong support for the work done and urged the development of a comprehensive action plan to be presented at the G20 meeting in July. The action plan will provide comprehensive, coordinated strategies for countries concerned with BEPS, while at the same time ensuring a certain and predictable environment for business.

Corporate tax policy, and in particular its international side, may need another look. Some rules and their underlying policy were built on the assumption that one country would forgo taxation because another country would be imposing tax. In the modern global economy, this assumption is not always correct, as planning opportunities may result in profits ending up untaxed anywhere. Also, the world has changed. Many rules are grounded in an economic environment characterised by fixed assets, plants and machinery and a lower degree of economic integration across borders, rather than today’s digital economy where much of the profit lies in risk-taking and intangible assets, such as patents and trademarks.

Not all issues are new, though, as our opening quote from President Kennedy shows. The aim of BEPS is to support countries’ efforts to shape fair, effective and efficient tax systems. Given its wide range of expertise, the OECD is in a position to deliver and meet the expectations of those committed to building better policies for better lives.

References and recommended sources

"BEPS: why you’re taxed more than a multinational" by Patrick Love, February 2013

OECD (2013), Addressing Base Erosion and Profit Shifting, OECD Publishing

OECD work on Tax

Base erosion and profit shifting

Aggressive tax planning

OECD Forum 2013 Issues

More OECD Observer articles on taxation

Subscribe to the OECD Observer including the OECD Yearbook

|

|

By Pascal Saint-Amans, Director, OECD Centre for Tax Policy and Administration

and Raffaele Russo, Senior Advisor, OECD Centre for Tax Policy and Administration

©OECD Yearbook 2013

|