Evaluation of development programmes

Evaluation Capacity Development Newsletter - March 2015

|

|

|

Theme : Competencies to improve the use of findings by policy-makers

Non-theme contributions |

Task Team for Evaluation Capacity Development

The DAC EvalNet Task Team for evaluation capacity development (ECD) is focused on developing and improving partnerships to strengthen the relevance, coherence and impact of our investments in evaluation supply and demand. The focus of the Task Team is on establishing a stronger evidence base of ‘what works’ in ECD, sharing and identifying opportunities for collaboration, and developing joint initiatives. The Task Team is currently chaired by the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID). This biannual ECD Newsletter represents an ongoing opportunity to inform others of ECD initiatives and opportunities for collaboration. It provides information on country, regional and global ECD initiatives, as well as new resources. This issue has been compiled by the ECD Task Team Chair.

|

Theme contributions |

||||

What competencies need to be developed amongst evaluation professionals to improve the use of findings by policy-makers?By: DFID, Stephen Porter Stimulating demand and promoting the use of evidence are issues for development evaluation professionals (evaluators, evaluation managers and commissioners). Two recent systematic reviews have emphasised the importance of contextual conditions in defining the use of evidence.[1] These reviews highlight that the more supply agents (e.g. evaluators and commissioners) are able to collaborate and form relationships with policy-makers (e.g. programme managers, senior civil servants and politicians), the more likely evidence is to be used. Deficits in the capacities of evaluation professionals to engage with policy-makers were identified in the 2010 Evaluation in Development Agencies report by the OECD. This report stated that the dissemination of evaluation has remained a passive exercise and lessons were not targeted at specific audiences in accessible and usable ways. Although competencies in engaging people are found in lists generated by the evaluation profession, traditionally they have not received the same attention as technical competence. Behind technical competencies there lies a thick body of research and perspectives. The literature on competencies focused on engaging policy-makers is, in contrast, thin. This means that there is territory to be further explored around the relational skills and approaches required by evaluation professionals in working with policy-makers. There is a range of current efforts to improve the relationships between evaluation professionals and policy-makers that help to highlight competencies that can be further developed; some of which are highlighted in this newsletter. Exploring communication competencies may provide an entry-point to better understanding the capacities evaluation professionals require to shape the way evaluation is seen and valued by policy-makers. One promising area is brand development. Brand is not a concept encountered in the evaluation or the capacity development literature. A brand for evaluation would be defined by connecting a specific idea, valued by policy-makers, to the qualities of an evaluation process. In other words, brand generates in target audiences an image of the total personality of the product or process. Think, for example, of Nike Air. The immediate vision that comes to mind is a person flying through the air with a basketball. Contained within the product is a vision of quality that appeals to the target market: high performance, innovation, achievement, winning.[2] The competencies in developing and maintaining a brand perspective in development evaluation emphasises the capacity to undertake a form of knowledge production that connects with policy-makers. Applying a brand perspective requires us to connect evaluation to the overarching institutional and psychological context of policy-makers. In turn, this places a requirement for all elements of the evaluation process to resonate with the quality dimensions in order to convey the brand. For example, if policy-makers believe that high quality development is responsive to the voice of poor people, then evaluations need to demonstrate that they can produce responsiveness to the poor. Brand seeks to develop interest and demand; people then will ‘buy’ the product or service. Evaluation use comes after and perhaps needs different activities. We invite further discussion on ways to change how demand can be stimulated and evaluation used through the application of communication competencies.

|

||||

| |

Rejoinder to 'What new competencies need to be cultivated amongst evaluation professionals to improve the use of findings by policy-makers?By: ARC Economics, Andy Rowe This article points to an important gap in evaluation. While most evaluators have long accepted that use and influence of evaluation is a central issue for the field and for evaluators undertaking evaluations, we have only considered this as it applies to the conduct and management of evaluations. While the approaches and methods that evaluators employ can strongly influence prospects for use, the discussion and debate about evaluation approaches and methods focuses almost exclusively on their technical merits – what is sometimes referred to as credibility[3]. If use is an important ambition of evaluation (and surely by now we should all accept this), then, as the article suggests, the use should be a strongly weighted feature when we discuss the merits of approaches and methods. This suggests that selection of methods should no longer be the exclusive domain of the evaluator but should be decided as part of the joint knowledge process. In terms of competencies, evaluators who can comfortably and effectively do this will need strong facilitation skills and understand that evaluation is not just about technique or precision, they will need to be more nimble, very adaptable and possess a wide range of technical competencies. Approaching use from the concept of a brand is intriguing. The potential value added lies in improving the salience of evaluation over and above what would have been achieved through undertaking evaluations as a joint knowledge process. Brand seems to represent an overarching connectivity of an evaluation office or practice to the interests whose views will strongly influence prospects for use. A successful brand perspective may improve the prospects that these interests will support engagement of programmes and projects that lie under their oversight in evaluation processes, thereby further improving prospects for use. Over time successful branding of use-inspired evaluation could contribute to improve mainstreaming of evaluation into governance. Also over time it could be a vehicle for developing the social capital between evaluated and evaluator leading to greater participation of the evaluated in identifying appropriate evaluation methods, and greater comfort of the evaluator with this. Those are worthwhile and important ambitions. Whether branding is a useful frame for this is an evaluation question for the future. But improving use is essential now and the DFID’s exploration of branding bears watching. A key underlying message in the DFID branding concept is that the highly skilled evaluation technicians that most evaluation competencies target are not what we need for use - the evaluators we need now are nimble adaptive evaluation facilitators with strong and wide ranging technical competencies.

|

|||

Rejoinder to ‘What new competencies need to be cultivated amongst evaluation professionals to improve the use of findings by policy-makers?’By: Stellenbosch University, Donna Podems The thoughtful question of, “What new competencies need to be cultivated amongst evaluation professionals to improve the use of findings by policy-makers?” encouraged further reflection on how (if, when, and why) policy-makers use evaluative information to make decisions; to which I did not know the answer. What skill set would an evaluator need to engage with and find answers to that question? To produce a product that would be used, the evaluator would need to thoroughly understand to what extent and in what circumstance each particular policy-maker would value and use data to inform his/her decisions. Turning this point on its head requires us to know: What would a policy-maker need to know to effectively engage with evaluation findings? This suggests one skill set that broadly describes an evaluator as an educator who has research and evaluation knowledge, and the skill set to effectively facilitate a process that engages a policy-maker, promotes good evaluation, and generates excitement and belief in evaluation processes and products. Engaging with end users and teaching them how to engage effectively with evaluation processes and evaluation findings means that it may not be the “evaluation product” that needs to be branded; rather it is the evaluation process, and the evaluation professional, that need branding. In moving forward it will be interesting to watch how DFID engages with this question and the subsequent competencies identified.

|

||||

|

Developing new competencies in evaluation professionalsBy: African Development Bank, Jayne Tambiti Musumba At the African Development Bank (AfDB), dissemination of findings, lessons and knowledge from evaluation is an active and continuous process, whereby knowledge management officers and communication specialists work alongside the evaluators. It is not an afterthought. The emphasis is on knowledge management and communications. Our evaluators are closely involved in knowledge management and communications activities, identifying the target audience, crafting messages, identifying the key products for specific audiences and suggesting dissemination channels such as organising community of practice events. They are also keenly involved in initiatives that bring them closer to the end users, in this case the policy-makers. The main two challenges of integrating knowledge management, communications and evaluation have been crafting technical content and feedback on the use of information. Evaluations tend to be heavy on technical information; therefore, the challenge is crafting messages to be non-technical, depending on the target audience. The other challenge is assessing the impact that these evaluations have. To do this we need to get feedback from policy-makers on how they have used the evaluation in developing policies or in making decisions; this is not always forthcoming. One initiative to involve policy-makers in evaluation and to help overcome these challenges is the establishment of the African Parliamentarians’ Network on Development Evaluation (APNODE). The overall aim of the network is to increase evaluation influence in government and legislative decision making and policy making in the APNODE member countries through two principal results: i) an improved national policy environment facilitating both the supply of evaluation as well as the demand for and use of evaluation in parliaments, public and public-related institutions in the APNODE member countries; and ii) raised awareness of and understanding by APNODE members and their respective parliaments of the benefits of evaluation results. A key lesson in interacting with policy-makers is not only the issue of adding new competencies to evaluators to better influence the use of evaluation findings, but also developing the capacities of policy-makers to be more receptive to the evaluation information and knowledge and knowing how best to use what is presented or shared with them. We believe that the soft skills needed for good collaboration (communication, conviction, facilitation and strategising) are important competencies that help in influencing policy-makers to use evaluation information.

|

|||

|

Working with parliamentarians for a better evaluation cultureBy: EvalPartners, Asela Kalugampitiya To ensure key policy decisions are based on evidence, policy-makers should demand and use evaluation in national decision making processes. In this context, parliamentarians are key stakeholders to ensure that countries have a robust national evaluation system that generates good quality evaluations to be used in national policy making. Institutionalising evaluation is a major step in making sure policy-makers make good use of evaluation and parliamentarians are aware that they should engage in evaluation and demand it. In the recent past, parliamentarians’ engagement in evaluation became significant and evident in different regions particularly in South Asia, Europe, Africa and Arab States. Parliamentarians emphasised their commitment for mainstreaming evaluation at national level since early 2013. Establishment of national evaluation policies together with political leadership is becoming part of work plans in these regions. In South Asia, a small group implemented their own Parliamentary Forum on Development Evaluation (PFDE) www.pfde.nt. The goal of the Forum is to advance the enabling environment for nationally owned, transparent, systematic and standard development evaluation process in line with the National Evaluation Policy at country level. This created discussion on why parliamentarians should engage in evaluation:

In March 2014, a group of African parliamentarians initiated their own Parliamentarians Network on Development Evaluation and issued the Yaounde declaration. Moreover parliamentarians attended EvalMENA conference held in Amman, Jordan in April 2014. At the EvalMENA conference, a panel “Linking Evaluation to Policy Making: the role of Parliamentarians” was conducted participated by parliamentarians represented from the region. The PFDE study on “Mapping status of national evaluation policies” and the report reveals only 20 countries have established national evaluation policies. Some countries are in the process of developing a policy. Evaluation community needs to work closely with legislators, policy-makers and other partners to establish national evaluation policies in respective countries. The case studies on national evaluation policies and systems in selected countries are also helpful for other countries in establishing a national evaluation policy. In line with the International Year of Evaluation 2015 and efforts for creating enabling environment for evaluation, parliamentarians’ role is becoming more and more important. The Global Parliamentarians Forum for Development Evaluation is being formed and will be inaugurated at the Global Evaluation Week to be held in Kathmandu, Nepal. National evaluation societies have the important role to engage parliamentarians and parliaments at national level dialogues.

|

|||

Non-theme contributions |

||||

|

Challenges for monitoring and evaluation in fragile and conflict affected statesBy: the Centre for Learning on Evaluation and Results for Anglophone Africa (CLEAR-AA), Kieron Crawley CLEAR AA has over the last two years carried out a number of exploratory studies that examine national monitoring and evaluation (M&E) systems across a range of selected African states. A small portion of the work has focused on states that are fragile and conflict affected (FCS), and while the scope is not yet comprehensive enough to draw wide conclusions[4], the findings have produced interesting insights as to why M&E and the decision making that it informs, remains a challenge in FCS.

M&E in a context of on-going sub-national conflict An enduring sub-national conflict provides major challenges to all levels of practical M&E data collection. In the case study, areas that are inaccessible to M&E teams constitute vast swathes of “dark data” that lead to an M&E jigsaw puzzle with very few pieces. The use of secondary data and/or data of suboptimal quality to fill these gaps more often than not leads to a “big picture” that comes loaded with risk for decision making. State security that is deployed to neutralise forces that threaten the state, relies on intelligence gathering for critical operational planning. In the case study this appeared to crowd out conventional M&E information flow within government creating a “stovepipe” to effectively channel information vertically upwards but that prevents the horizontal sharing of information that is crucial to a well-functioning M&E system.

M&E shaped by humanitarian crisis Sub-national conflict is in many instances accompanied by a humanitarian crisis that draws in a response from international agencies. In the case study, government, UN Agency and INGO M&E practice was driven by the need to account to donors for substantive quantities of international aid. A consequence of the justifiable emphasis on coordinating the efficient delivery of aid is that M&E shifts focus from evaluating longer term results to monitoring inputs and activities. Under these circumstances, crucial M&E data that informs decision making as to when to transition from relief to development remains elusive. Longer timeframes in terms of donor contracting for aid interventions may help embed a longer term M&E vision.

Collaboration and trust between key M&E stakeholders Collaboration and trust between M&E stakeholders is key to ensuring that pathways for M&E data remain open and effective. Fragility and conflict tend to create trust deficits and information barriers through which data is unlikely to pass. In addition, certain classes of data (e.g. relating to health epidemics or malnutrition) can become politically sensitive and selectively shared. In the case study it was evident that while trust and collaboration within tightly defined humanitarian clusters was strong (allowing M&E information to flow relatively easily), trust between civil society, international agencies and government was fragile thereby greatly constricting the free flow of M&E information between them. One approach to tackling the M&E trust deficit in FCS may be to strengthen existing networks while pursuing a parallel strategy to nurture links between them.

Political vision and championship for M&E Political champions who can push the M&E agenda (often in the face of opposition) are considered crucial to building any M&E system. In FCS with less than democratic regimes, the political space for those who diverge from the official line may be narrow. In the case study, the political risk to internal change makers was substantial. The most promising strategy for change in these circumstances may be to support mid-level “technical champions” whose heads are just below the parapet.

M&E and the ideology of the state While not often overtly stated, M&E systems work best in democratic systems where accountability, transparency and a demand for evidence of performance from citizens ease the flow of information and unblock potential barriers to its circulation. Fragile and conflict affected states may have weak democracies or indeed be transitioning through periods where substantial democratic rights have been suspended. Accountability to, and demand from citizens falls away under these circumstances. While the case study confirmed that an institutionalised government M&E system may be counter to the political economy on which the current regime relies, peace agreements and the bodies set up to administer them may constitute an ideological foundation on which to incrementally “build belief” in M&E.

|

|||

|

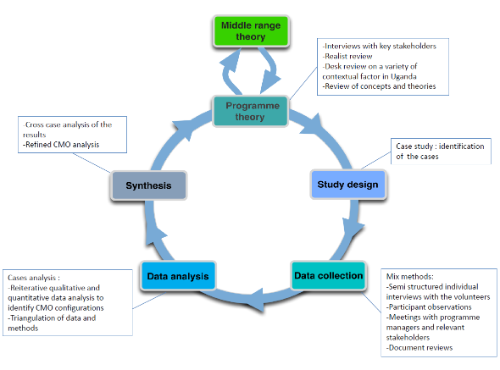

Strenghtening RC/VC volunteer-based community approaches: IFRC realist multiple explanatory case studies By: the Health Department of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies Worldwide, the Red Cross and Red Crescent (RCRC) National Societies (NS) are training and supporting volunteers to improve the health of underserved communities and to strengthen their resilience. Volunteers are the backbone of the RCRC and many NS report difficulties attracting, motivating and retaining volunteers. These challenges have led to the Health and Volunteering Departments developing a research programme to better understand why, how and under what circumstances volunteer motivation and performance can be enhanced by appropriate managerial strategies. Because RCRC Community Based Health capacity building interventions are complex and highly context-dependant, the research requires appropriate methods. Traditionally, the RCRC evaluates its programmes using the summative evaluation approach to assess programme implementation effectiveness and relevance. These evaluations are useful, but they fail to provide a clear answer on how to manage and support volunteers. Therefore, the research team has used a "realist approach", which is suited to evaluate complex interventions and follows a circle, that starts and ends with a programme theory (Figure 1). |

|||

|

Figure 1: The realist evaluation cycle used for the studies

|

||||

|

To develop the capacity to undertake this form of evaluation, a partnership is being built with academic experts (from the Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp) on the realist approach and is financially supporting the work of students. The capacity development plan includes implementing a continuing series of realist seminars (attended by representatives of organisations, such as, Google, DFID, WHO – GHWA, Volunteer Service Overseas and many academic partners), training of evaluators, partaking in technical working groups, participating and presenting at conferences and workshops, disseminating results (such as publication in the British Medical Journal) and developing a steering committee. The first study took place in Kampala (Uganda) in March 2014 where two cases were selected. "Case" refers to the RC branch unit responsible for programme implementation and coordination in one district (Figure 2). After in depth exploration of a limited number of cases, additional cases will be chosen to refine the initial assumptions. The findings from each case will inform the next study. Through this process each iteration will enable us to formulate plausible explanations of how interactions between actors, leadership, managerial practices and organisational context influence volunteer motivations and work behaviour. In doing this our own capacity will iteratively be developed as we better understand key mechanisms for volunteer motivations. |

||||

|

Figure 2: First study in Uganda - group discussion

|

||||

|

Proceedings from the third international conference on national evaluation capacitiesBy: UNDP, Independent Evaluation Office The Independent Evaluation Office of UNDP is committed to using national evaluation systems as a way to strengthen national ownership over development processes and engaged in promotion National Evaluation Capacities among partner countries. Conferences, such as the one in 2013 in Brazil, provide a forum for discussion of evaluation issues confronting countries and enable participants to draw on other countries’ recent and innovative experiences. The previous two national evaluation capacities conferences held in Morocco and South Africa emphasised the need to build better institutional capacities to manage development programmes. National systems that facilitate independent and credible evaluations play an important role in achieving these priorities by generating evidence and objective information on how improvements can be made. The proceedings from the latest conference in Brazil capture key messages and outcomes from the conference, contributing to knowledge sharing and South-South co-operation among countries to strengthen evaluation related efforts. To increase relevance for policy-makers, this publication presents a set of four commissioned papers that provide a conceptual framework for the conference’s theme. It also includes 31 country papers (the majority of which were authored by conference participants) that provide national perspectives on the issues of independence, credibility and use of evaluation. |

|||

|

[1] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3813708/; http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/14/2 [2] http://www.slideshare.net/Ahmed_Coucha/brand-managment-nike-building-a-global-brand-case-analysis [3] R. B. Mitchell, W. C. Clark, D. W. Cash, & N. M. Dickson, Global Environmental Assessments. Cambridge: MIT Press; Clark, W. C. and N. M. Dickson (2003). "Sustainability science: the emerging research program." Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100(14): 8059-8061. [4] The study in question was carried out in an African State experiencing an ongoing sub national conflict and associated humanitarian emergency |

||||

|

||||

Related Documents