Lessons from PISA: Challenging some of our commonly-held assumptions about education in Panama

By Nadia De Leon

|

Tania Johnson

|

Filippo Besa

|

In the past decade, the Panamanian government has taken several steps to improve the country’s education system. With the implementation of policies such as conditional cash transfer programmes like PASE-U, previously known as the Beca Universal, the government made significant progress in expanding the coverage of the education system. Through these policies, families received financial assistance from the government provided they enrolled their children in school.

Intending to evaluate the Panamanian education system's strengths and weaknesses, the Ministry of Education decided in 2016 to participate again in PISA after a decade long break from the programme. Panama was the only country to participate in both PISA 2018 and PISA for Development Strand C, a project that assesses reading and mathematics skills of 14-16 year-olds that are not enrolled in school. By participating in both assessments, Panama achieved a unique 360-degree perspective of the learning achievements, environments and challenges for youth in and out of its education system.

In September 2020, MEDUCA published its PISA national report on its website, which includes an extensive analysis of the country's PISA 2018 and PISA for Development Strand C results. The report revealed disparities in educational achievement and school resources among different population groups. Yet, it also provided evidence that brought into question many commonly held assumptions regarding the country’s education system. Let’s build on some of the report's main findings to demystify two common beliefs about educational opportunities and resources that PISA results helped challenge.

Assumption 1: Private education is better

In Panama, a widespread belief is that private school students will outperform public school students in most, if not all, assessments. When looking at the disparities in the reading, mathematics, and science performance of public and private school students and not controlling for other school and student characteristics, this belief seems correct. On average, students from private schools tend to perform better than students from public schools. Before controlling for school and student characteristics, there is a 70-to-80 score-point difference in all three domains in favour of students enrolled in private schools, with the most polarized domains being science and reading.

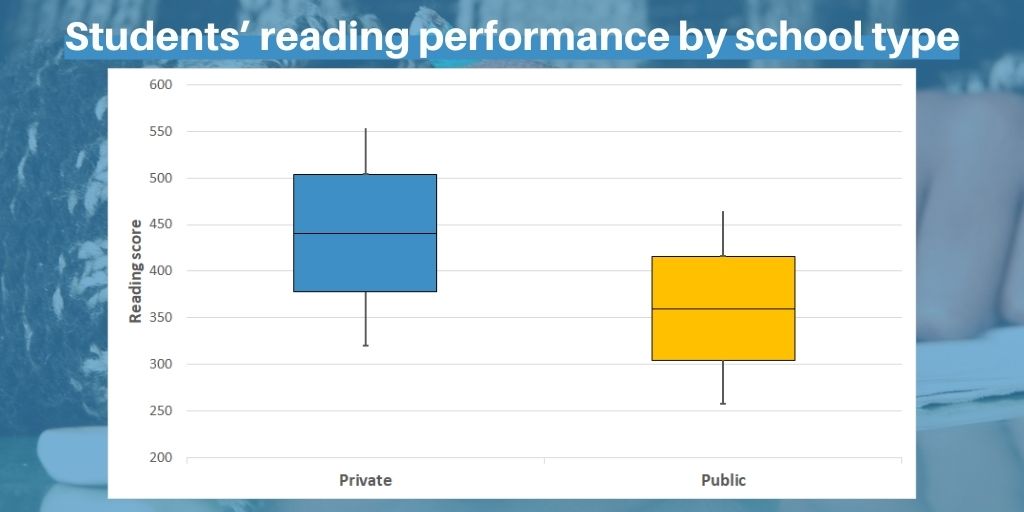

However, when looking at the distribution of student performance in reading, mathematics, and science by school type, there is a substantial overlap, about 65% to 75%, in the performance between public and private school students. The figure below shows the distribution of the students' reading performance by school type; although the top 25% of private school students score higher in reading than the top 25% of public-school students, it appears that there are also private school students performing at the same level as their peers in public schools in reading.

The idea behind the common belief that private education is better is that private schools tend to have better resources than public schools. Therefore, they can offer their students a better-quality education. However, PISA results also revealed that private education is not always synonymous with better resources. From the school questionnaire results, we learned from private school principals that some private schools lack the necessary educational resources and staff to educate their students. About one-in-three private school students attend a school whose principal reported a level of educational resources or staff below the average level for public schools.

Assumption 2: If young people are not in school, they are not learning

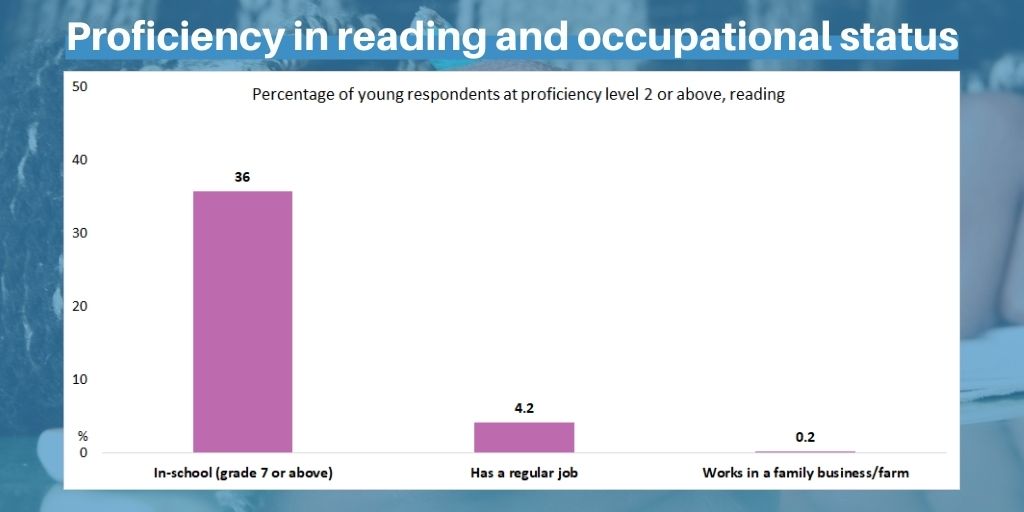

Another common belief is that if young people are not in school, they are not learning. At first glance, this assumption appears to be true. A much higher percentage of students, who are in grade 7 or above, reached the minimum proficiency levels (level 2) in reading and mathematics than the youth not enrolled in school. For example, 36% of students reached proficiency level 2 (the SDG 4 benchmark) in reading and 19% in mathematics, compared to 4.1% and 1.7% respectively of the youth from rural areas and indigenous territories that are not enrolled in school.*

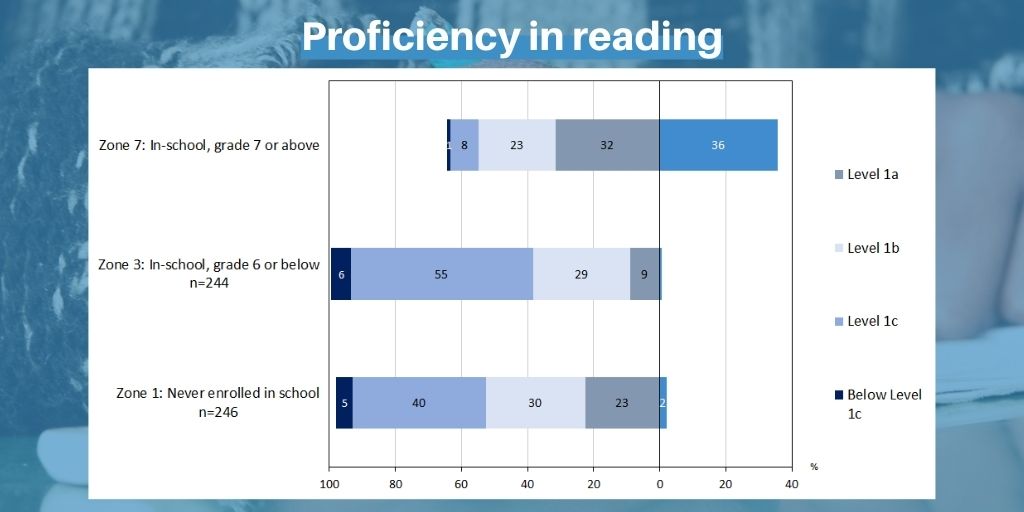

However, an analysis of the results of the youth not enrolled in school by "zones of exclusion", a categorisation method used in the work of the Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions and Equity (CREATE), and UNESCO's and UNICEF's out-of-school children initiative, provides us with some fascinating insights, which can be found in the national report. The analysis groups the youth by their highest education level. Comparing the proficiency levels of youth that were never enrolled in school (zone 1) with those who remained in school but were in grade 6 or below at the time of the survey (zone 3) is of particular interest. The percent of youth, who never enrolled in school (Zone 1) and achieved higher proficiency levels in reading is larger than the percent of those in Zone 3, those enrolled in grade 6 or below at the time of the survey (see figure below). In particular, a larger percent of youth in Zone 1, those that never enrolled in school, than in Zone 3, those who were in grade 6 or below, achieved proficiency levels 1b and 1a in reading.

Although proficiency levels 1a and 1b are still below the SDG 4 benchmark for minimum proficiency levels (level 2), it is interesting that about half of the youth in Zone 1 (those that never enrolled in school) were able to develop literacy skills that allow them to understand the literal meaning of longer sentences or passages and make simple connections between adjacent pieces of information despite not having received formal education.

From PISA-D Strand C's results, we also learned how other contextual factors can provide learning opportunities for young people who are not in school. For example, the youth, who were not enrolled in school and had a paying job at the time of the survey, seem to have more opportunities to learn and develop essential reading and mathematics skills than their peers that worked on a family farm or a family business. The figure below shows the proficiency levels of youth not enrolled in school by occupational status.

These young people in Zone 1 are clearly using alternative opportunities to schooling to develop their reading and mathematics skills. It is interesting to note that these alternative approaches to learning have resulted, in some cases, in higher levels of achievement than their peers in Zone 3, who, although were enrolled in school, were academically “behind.” In other words, in the same way that school doesn’t always equate to learning, being out-of-school doesn’t always equate to not learning. This particular finding causes us to reconsider some traditional concepts about learning environments and opportunities. It highlights the need to “think outside of the box” when developing educational programmes and policies to help reintegrate young people who are not enrolled in school back into the education system.

Rethinking and challenging commonly held assumptions about educational resources and opportunities with data is necessary for effective policymaking. In Panama, the PISA results prompted policymakers to re-evaluate and further develop existing initiatives that offer educational opportunities to youth not enrolled in school and programs that support public and private schools. Lastly, it also helped decision-makers consider other creative solutions to improve the quality of education and increase the value-added from schooling for young people in Panama.

*Panama’s sample of the youth not enrolled in school is representative of the 14- to 16-year-old population in rural areas and indigenous territories

Related Documents