Measuring masculine norms to better understand the invisible barriers to women’s economic inclusion

March 2021 - Over the past 20 years, women’s global labour force participation rate has remained constant at around 50%, while the gender gap in labour force participation remains high at 27 percentage points (ILO, 2020; OECD, 2020). This lack of progress highlights the failure to promote women’s inclusion in the labour market and in employment. In particular, discriminatory social institutions – including laws, social norms and commonly accepted practices—constitute some of the most powerful driving forces behind both the unequal outcomes and the slow progress (OECD, 2019). Social norms are especially important as they function as often unspoken “rules of the game” governing societies’ expectations and beliefs about what is and is not acceptable. Social norms pertaining to gender are especially strong and guide socially accepted understandings of men and women’s roles in society.

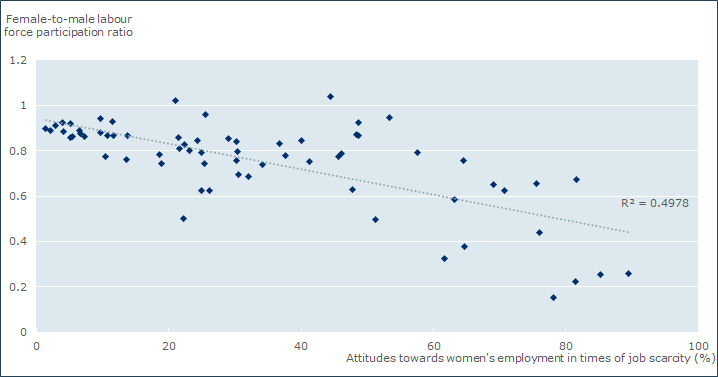

Recent research conducted by the OECD Development Centre shows that among these, restrictive masculinities[1] prevent women’s full inclusion in the labour market by promoting rigid stereotypical beliefs (OECD, Forthcoming). Among these beliefs are the idea that “men should have more rights to a job than women when jobs are scarce”. Data from eight countries[2] show that more than 70% of the population still agrees with this statement (Haerpfer et al., 2020). More generally, the notion that men are breadwinners while women are caretakers promotes the idea that men are primary earners and women’s income is largely supplementary. As such, women’s economic contribution is deprioritised and undervalued, constraining women’s labour force participation and perpetuating large employment gaps between men and women (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Norms of restrictive masculinities constrain women’s labour force participation

Female-to-male labour force participation ratio by share of the population declaring that men should have more rights to a job than women when jobs are scarce

|

| Note: Attitudes towards women's employment in times of job scarcity is measured as the percentage of respondent agreeing or strongly agreeing with the statement "When jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women". Data are available for 67 countries. R² = 0.4978. Source: Haerpfer et al. (eds.) (2020), World Values Survey: Round Seven – Country-Pooled Datafile, http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV7.jsp; and ILOSTAT (2020), Statistics on the working-age population and labour force, https://ilostat.ilo.org/topics/population-and-labour-force/ |

To address these restrictive masculinities and to stop them from stalling women’s inclusion in the labour market, policy makers need more data. In particular, data measuring the norms associated with these restrictive masculinities should include attitudinal indicators, which show the extent to which men and women support the vision of manhood upheld by restrictive masculinities. However, the OECD Development Centre‘s recent research shows that very few indicators measuring these attitudes are available and comparable across time and location, and large data gaps remain in critical areas, especially those concerning the norms behind occupational segregation (OECD, Forthcoming). The forthcoming publication outlines good practices for data collection that will ensure the success of future statistical activities seeking to collect data on masculine norms:

- Measure the attitudes of both men and women, together as masculinities are not self-directed by individual men but are collectively shared social norms and expectations about what men and boys do and what they ought to do.

- Measure men’s perception on what their community/society believes as social sanctions are an important barrier to changing social norms and men may choose to stick to restrictive scripts of manhood if the social cost of being different—and more gender-equitable—is high.

- Prioritise comparability across time and location in order to measure changing masculine norms and assess whether macro-phenomena (such as the Covid-19 crisis), social movements (such as #MeToo) and national policies are making a difference.

- Account for the role of age as masculine norms change throughout men’s lifecycles and consequences induced by restrictive masculinities may vary among age groups such as boys, young men and older men.

- Focus on the attitudes of key gatekeepers – e.g. teachers, policy makers, law enforcement, judicial officials and healthcare workers—through dedicated qualitative data collection procedures such as Focus Group Discussions and Key Informant Interviews.

In addition, the report recommends going beyond the collection of attitudinal data, to investigate the messages legal frameworks send about men’s roles in societies, as well as the prevalence of certain social practices.Not only do legal frameworks often reflect the social norms that govern societies, but they also define men and women’s opportunities to take on certain roles. For example, legal frameworks promote the idea of “manly” jobs and fuel segregation in the labour force by prohibiting women’s entry into some professions.At the same time, social practices may indicate an adherence to certain masculine norms.When social norms are internalised, they may be observed through certain behaviours. For example, large gender gaps in managerial positions may be the reflection of restrictive norms stating that men are better workers and leaders than women are.

References

-

Haerpfer, C. et al. (eds.) (2020), World Values Survey: Round Seven – Country-Pooled Datafile

-

ILOSTAT (2020), Statistics on the working-age population and labour force

-

OECD (Forthcoming), Man Enough? Measuring masculine norms to promote women’s empowerment, OECD Publishing, Paris.

-

OECD (2020), “Labour Market Statistics: Labour force statistics by sex and age: indicators”, OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics (database)

-

OECD (2019), SIGI 2019 Global Report: Transforming Challenges into Opportunities, Social Institutions and Gender Index, OECD Publishing, Paris

Further reading

- Park, H. and Woleske, G. (2021), “Three root causes of violence against women and how to tackle them”, Development Matters, 18 January 2021

- OECD (2019), Engaging with men and masculinities in fragile and conflict-affected states, OECD Development Policy papers, OECD Publishing, Paris

Browse the SIGI and the Gender, Institutions and Development Database.

[1] Restrictive masculinities are social constructs that relate to rigid and inflexible notions – shared by both men and women – about how men behave and how they are expected to behave to be considered “real” men.

[2] Bangladesh, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kyrgyzstan, Myanmar, and Pakistan.

Related Documents