Education

Education Policy Outlook Snapshot: Norway

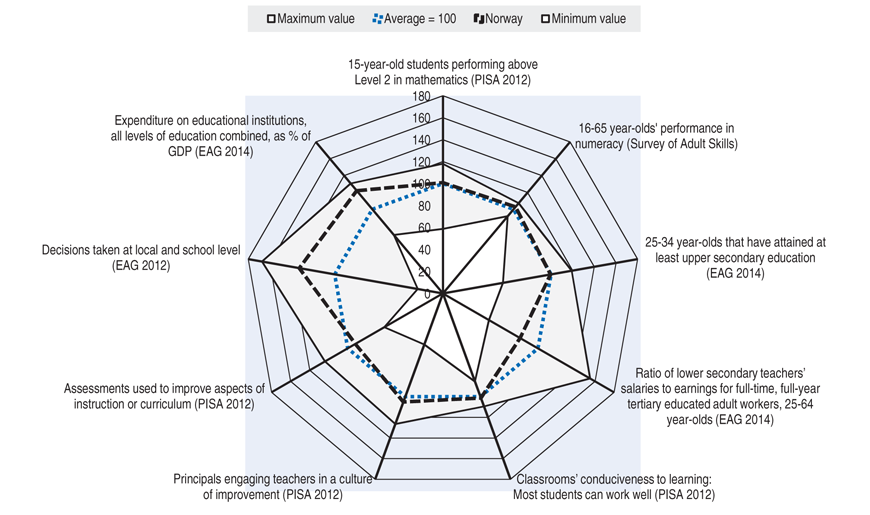

Norway’s educational contextStudents: Norway performs above the OECD average in reading, at around average in mathematics and below the OECD average in science in PISA 2012, with the lowest impact on socio-economic factors on students’ performance among OECD countries and unchanging performance across PISA cycles. Some system-level policies help enhance equity in Norway. Early childhood education and care (ECEC) usually starts at age 1 (the earliest age across OECD countries), and the enrolment rate of 3-4 year-olds in ECEC is above the OECD average. Norway has comprehensive and compulsory education from age 6 to 16. At upper secondary level, attainment rates are around the OECD average, and there is a strong supply of upper secondary vocational education and training (VET), with an above-average enrolment rate. Tertiary education attainment rates are higher than the OECD average, resulting in a highly skilled workforce. Adults (16-65 year-olds) have above-average proficiency levels in literacy and numeracy compared to other countries participating in the Survey of Adult Skills, with younger adults (16-24 year-olds) scoring lower than the average and, unlike the situation in most other countries, lower literacy skill levels than the adult population as a whole. Norway has the lowest rate of unemployment among OECD countries. Institutions: In Norway, schools’ autonomy over resource allocation (such as hiring and dismissal of teachers) is around the OECD average, while autonomy over curriculum and assessment is below average. Learning environments in schools are less positive than the OECD average, according to views of students at age 15. Lower secondary teachers are required to follow four years of pre-service training including mandatory teacher training. In secondary education, teaching time is lower than the OECD average, while in primary education it is higher than the OECD average. In both primary and secondary education, salaries are above average, and class size is on average smaller than in other OECD countries. A lower proportion of teachers in Norway than the TALIS average consider that the teaching profession is valued in society and would choose to work as teachers if they could decide again. Also, school leaders focus more on administrative than pedagogical tasks. When appraisal takes place, it often leads to opportunities for professional development activities or a role in school development initiatives. Norway has developed a multi-faceted system for evaluation and assessment in schools, including quality assessment, which can be completed and made more coherent to support effective evaluation and assessment practices. The Norwegian Agency for Quality Assurance in Education (NOKUT), an independent government agency, provides quality control for tertiary education. System: Governance of the education system is shared between the central government and local authorities. Norway’s central government sets the goals and framework, while municipalities run primary and lower secondary schools and counties run upper secondary schools. Municipalities also fulfil the right to a place in pres-school for all children from age 1. Lower secondary schooling decisions are mostly taken at the local level, with just a few decisions taken at the state level, while tertiary institutions are mostly autonomous in their decisions, including those on how they allocate resources. Norway has generous funding at all levels of the education system. Public education is free, except at pre-primary level where parents pay fees. Expenditure on education institutions as a percentage of GDP (for all educational levels combined) is one of the highest among OECD countries. Selected indicators compared with the average  Click here to access the underlying dataNote: For each indicator, the absolute performance is standardised (normalised) using a normative score ranging from 0 to 180, where 100 was set at the average, taking into account all OECD countries with available data in each case. See www.oecd.org/edu/policyoutlook.htm for maximum and minimum value countries. Source: The Norway Snapshot was produced combining information from Education Policy Outlook: Australia, (OECD, 2013) with OECD data and the country’s response to the Education Policy Outlook Snapshot Survey (2013). More information on the spider chart and sources is available at www.oecd.org/edu/policyoutlook.htm. Click here to access the underlying dataNote: For each indicator, the absolute performance is standardised (normalised) using a normative score ranging from 0 to 180, where 100 was set at the average, taking into account all OECD countries with available data in each case. See www.oecd.org/edu/policyoutlook.htm for maximum and minimum value countries. Source: The Norway Snapshot was produced combining information from Education Policy Outlook: Australia, (OECD, 2013) with OECD data and the country’s response to the Education Policy Outlook Snapshot Survey (2013). More information on the spider chart and sources is available at www.oecd.org/edu/policyoutlook.htm.

Key issues and goalsStudents: Norway faces the challenge of ensuring that students remain in school until the end of upper secondary education. Continuing to promote equity while fostering student motivation and excellence is also of high interest. Institutions: Efforts have been made to improve learning conditions for students by enhancing pedagogical support and strengthening assessment. System: Norway aims to ensure capacity-building and consistent implementation across all municipalities. Optimising resources and policy implementation strategies in a context of decentralised decision-making is also key. Norway also needs to improve the coherence and responsiveness of its skills system, focus on developing relevant skills to achieve its economic and social goals, and on activating and using these skills effectively.

Selected policy responses

|

||||

| Please cite this publication as: OECD (2015), Education Policy Outlook 2015: Making Reforms Happen, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264225442-en |

| Back to the country profiles page |

Permanent URL: www.oecd.org/edu/policyoutlook.htm

OECD work on education: www.oecd.org/education

Related Documents