Inclusive societies and development

Youth well-being policy review of Jordan: A 60 seconds guide

|

What is the Youth Well-being Policy Review of Jordan?

|

The Youth Well-being Policy Review of Jordan provides an in-depth analysis of the situation of young Jordanians through a multi-dimensional approach and provides policy recommendations to improve youth well-being. The review:

|

|

How's life for young Jordanians?

|

Over the last two decades, Jordan has made considerable socio-economic progress. With one-third of the population aged 12-30, it has a tremendous development potential. However, young Jordanians still face multiple challenges. Young Jordanians enjoy wide access to education and are better educated than their parents — 60.5% of 25-29-year-olds have a secondary or higher degree — yet, both quality and relevance need to improve. In 2015, Jordan’s results in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) were well below the OECD average: in mathematics, Jordan ranked 66 out of 72 countries, while in reading it ranked 63 out of 72. The high unauthorised student absenteeism — 43.4% of students miss at least one day of school every two weeks — partially contributes to these low performances. Despite Cambodia’s economic growth, young Cambodians face multiple challenges: according to the Youth Multi-dimensional Deprivation Indicator (Y-MDI) developed by the EU-OECD Youth Inclusion project, one young person in five is deprived in at least two well-being dimensions, including health, employment, education and civic participation, while 40% fare poorly in at least one dimension, mostly in education. The health situation of young Jordanians has improved in recent years. The mortality rate per 100 000 young people declined from 91 in 2005 to 71 in 2015 and so did adolescent fertility rates — from 30.1 per 1 000 women aged 15-19 to 22.7. This is considerably below the MENA average and comparable to the OECD average. Yet several challenges remain, such as insufficient knowledge about sexual and reproductive health (SRH) (90.7% for young women aged 20-24), the prevalence of teenage smoking (24% among youth aged 14-15) and obesity (10.6% among youth aged 15-18). Jordanian youth have little trust in parliament (22.7%) and political parties (11.7%). Moreover, youth civic engagement is limited. While youth recognise the importance of political participation, only a very small percentage are members of formal civic groups: 2.7% of a charitable society and 2.3% of a youth, cultural or sports organisation. Lacking time, consultation and engagement mechanisms, as well as insuffi cient preparation through school are the main obstacles to participation. Close to one-third of young people in Jordan are neither in employment nor in education or training (NEET). The NEET rate among young women is triple that of young men (43.8% vs. 14.5%). This is partly explained by traditions and domestic tasks. Young Jordanians who do work often take informal jobs that do not match their qualification and receive poor wages: in 2015, 37.5% of young workers were informal, half of them did not have qualifications matching their occupation and 59.4% received Given the strong growth of medium-skilled professions, TVET can improve youth’s labour market outcomes. However, quality, relevance, co-ordination and governance need to improve for it to become an attractive alternative for young Jordanians. |

|

Did you know...?

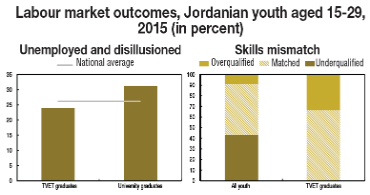

Unemployment is lower amongst TVET graduates (23.8%) than university graduates (31.2%) and national average (26.2%). TVET graduates are also more likely to have the skills matching their profession (65.9%) compared to all youth (47.2%).

Note: Disillusioned youth are those who would like to work but i) have not sought work because they did not know how or where; ii) believe themselves unable to find work with their skills; iii) looked but did not find work; iv) believed themselves too young to work; and v) reported no jobs available in their area. |

|

|

How to address those challenges?

|

The role of young people as agents of economic and social development is increasingly recognised in the political discourse. However, the government’s fi rst National Youth Strategy (2005-09) was never followed by a comprehensive youth policy or strategy, due to institutional instability, financial constraints and lack of political ownership. The development of the National Youth Strategy (2018-2025) has been underway for a prolonged period but remains at an inception stage. Currently, Jordan lacks a comprehensive framework to regulate and co-ordinate youth legislation, policies and interventions across different sectors. Although the responsibility of youth affairs falls under the mandate of the Ministry of Youth (MoY), the range of issues affecting youth can hardly be addressed by one ministry. To ensure the successful implementation of youth policies, government institutions, royal NGOs and international actors need to work more closely together. |

What can the government do?

|

Address youth as a transversal theme in Jordan’s public policies

Align technical and vocational education and training with the demands of youth and firms

Facilitate active citizenship and involve youth in policy-making processes

|

Related Documents