A long way before turning promises into progress: discriminatory laws and social norms still hamper gender equality

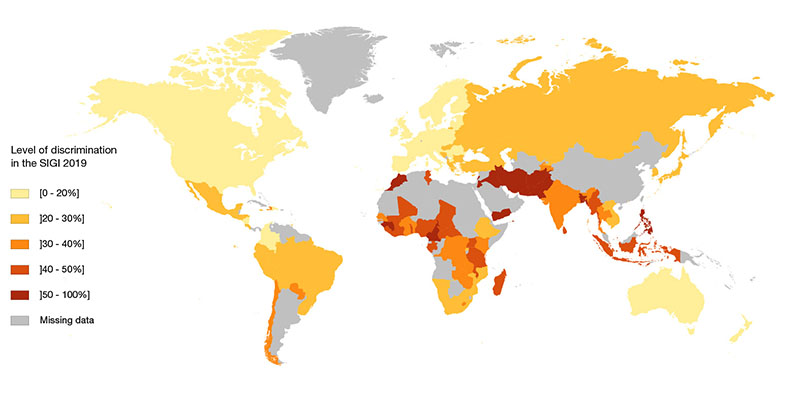

March 2019 - Legal reforms and transformative gender policies and programmes conducted by governments, civil society, philanthropy and the private sector are starting to pay off. The Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI) 2019 results indicate that the global level of discrimination in social institutions – i.e. formal and informal law, social norms and practices - is 29%, ranging from 8% in Switzerland to 64% in Yemen (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1. SIGI 2019 results

|

| Note: Higher SIGI values indicate higher inequality: the SIGI ranges from 0% for no discrimination to 100% for absolute discrimination. Source: OECD (2019), Gender, Institutions and Development Database, https://oe.cd/ds/GIDDB2019 |

This relatively good performance is explained by increasing political commitment to the elimination of gender inequality and shifts in some social norms that are detrimental to equality at the global level. New legislation has enhanced equality and abolished discriminatory laws. For instance, since the last edition of the SIGI, 15 countries strengthened their legal frameworks to delay the age of a first marriage by eliminating legal exceptions; 2 countries have eliminated discriminatory legal provisions related to women’s inheritance; 15 countries enacted legislation to criminalise domestic violence; and 3 countries have criminalised Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) since 2014. Similarly, some social norms that are detrimental to equality have become less prominent. For instance, social acceptance of domestic violence decreased from 50% in 2012 to 37% in 2014 and 27% in 2018, which has important consequences for women and girls’ well-being. In Sudan, for example, the proportion of the population supporting FGM went from 27% to 18% between 2014 and 2018. The shift in attitude and the resulting decrease in FGM prevalence make a compelling case for public health policy to eradicate the practice altogether.

However, bottlenecks are persistence explaining why it will take over 200 years to achieve gender equality:

- Discrimination in the family seems to be the most difficult dimension to address, regardless of the region or the income level. Social expectations towards women’s reproductive and caring role are still widely widespread and women continue to bear 75% of the burden of unpaid care and domestic work. Moreover, women’s status by law is still subordinate to their husband’s authority: 41 countries recognised a man only as the head of households, while in 27 countries women are required by law to obey their husbands.

- Despite women’s physical integrity having attracted much attention, guaranteeing women’s and girls’ sexual and reproductive health and rights, as well as their freedom from violence, remain key challenges. The social acceptance of domestic violence – more than one in four women justifies men’s use of violence against their wife/partner- explain partially the high prevalence of survivors.

- Discrimination against women’s workplace rights is still a universal issue with 94 countries restrict women’s access to employment and 50% of the global population believing that children will suffer when the mother is gainfully employed outside the home and 17% do not find it acceptable for a woman family member to have a job.

Women’s political voice is deeply entrenched social expectations of what a woman’s role in public life should be: 69 countries have no legal quotas or special measures or incentives for political parties to promote women’s political participation; and almost half of the world’s population (47%) believe that men make better political leaders than women do. This partially explains why fewer than 24% of parliamentary seats are occupied by women, only two points better than in 2014

Further Reading

- OOECD (2019), SIGI 2019 Global Report: Transforming Challenges into Opportunities, Social Institutions and Gender Index, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/bc56d212-en

-

OECD (2018), Burkina Faso SIGI Country Study (in French)

-

OECD (2017), The Pursuit of Gender Equality: An Uphill Battle

-

ILO and Gallup (2017), Towards a better future for women and work: Voices of women and men

-

OECD (2014), Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI) 2014 Synthesis Report

Browse the SIGI and the Gender, Institutions and Development Database.

More data on the OECD Gender Data Portal

Related Documents