Africa’s choice: Business-as-usual or a green agenda?

|

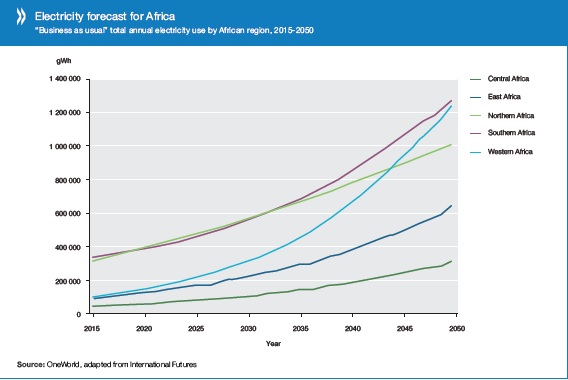

The Paris Agreement on climate change signals the end of business as usual for energy industries. For the first time in history more than 150 developed and developing countries have promised to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But how binding are these agreements? And do they provide impetus for local action in Africa? The 2015 Paris Agreement revived the global process of curbing global warming. It has been hailed as a turning point for the low-carbon economy on the road to achieving planetary sustainability. Because of the political unity that stands behind the agreement, it also sends a strong economic signal to invest in green energy. All this comes at a time when Africa is struggling to translate economic growth into structural transformation. Thus a review of industrial policy in Africa is necessary. A regional approach to diversifying economic structures, alongside investment in infrastructure, particularly energy, water and transport, will establish the foundations essential to further economic growth and structural change. With this, climate change brings increased risks (droughts and floods, rising temperatures and altered rainfall patterns), to which Africa, with its infrastructure deficit and inadequate institutional capacity, is particularly vulnerable. Consequently, African countries need to build resilient economies. The Paris Agreement, and the preceding Sustainable Development Agenda for 2030, provide clear directions for future growth and investment. The Paris Agreement is global, but implementation depends heavily on decisive national action. A lot hinges on governments and industries deciding to take committed action now and ratcheting up future ambition. This will depend on perceptions of the related gains and losses. In preparation for the Paris negotiations, countries stated their non-binding Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs). Realising these intentions is essential to a global low-carbon future while advancing sustainable development. The process and reasoning builds on emission reductions commitments from 187 countries, starting in 2020. For the first time in history rich and poor countries have promised to reduce carbon emissions and to increase these reductions over time. Current commitments are not yet sufficient to limit global warming to the desired 1.5°C, but, the Paris Agreement binds all countries to regular reviews on progress. Africa’s imperative African countries have a choice: continue along a business-as-usual path or help lead the way to the new global low-carbon economy. Critically, the Paris Agreement signals the end of business as usual for global energy industries and sounds a death knell for fossil fuels. In sum, it is evident that future energy investments will need to be compatible with a zero-carbon world. Currently, the 6.5% of global GDP spent on fossil fuel subsidies translates annually into around $5.3 trillion. Redirecting part of these funds makes the growth of renewables in energy-poor regions such as Africa plausible. In Africa, the imperative for transformation to renewable energy is essential to achieving structural transformation. Africa is endowed with substantial renewable resources, with adoption being about improved technologies and favourable pricing. The possibilities of both are evident in emerging economies around the world, providing a meaningful way of achieving the ambitious global warming goal embedded in the Paris Agreement. Thus the focus of energy transformation in Africa is first and foremost a sustainable development prerogative. There are three primary reasons for this. First, the global renewable energy market has taken hold, with 2015 setting a record for investment. Prices for some renewables are steadily decreasing, spurring investors to find new markets. Africa presents a substantial, relatively untapped market where investors require government support to open market access. Second, Africa needs a regional approach to economic restructuring, improving regional integration and opening trade to facilitate infrastructural investments, particularly in the energy needed to power economic transformation. Under business as usual, Africa will increase its reliance on fossil fuel imports by 2050, assuming only marginal growth in industrialisation. Moreover, Africa’s reliance on fossil fuel imports will widen dramatically as countries attempt to close the supply-demand gap. Third, although many factors are to blame for Africa’s colossal energy deficit, the biggest problem, and opportunity, is population growth and the unstoppable influx of people into the continent’s cities. Herein lies one of the most important incentives for African countries to pursue renewables. The rapid rate of urbanisation is a major challenge for cities throughout the continent, where the historical deficit of infrastructure will see energy crises looming large. If Africa continues along its current path reliance on fossil fuel imports will increase, subjecting countries to unacceptable levels of energy insecurity. The United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) places energy consumption in urban areas at no less than 75% of total consumption. The only solution is renewables, using growing urban centres as hubs of innovation and skills.

Continued population growth means the scale of these challenges will only grow. By 2050, Africa’s population is forecast to double from about 1.2 billion people in 2015 to almost 2.5 billion. Scenarios developed for the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) by OneWorld Sustainable Investments suggest that most of this growth will be in cities, with the urban population reaching more than 55% of the total by 2050. Throughout Africa, population growth is the main reason for the increasing demand for energy. But a growing middle class, with people earning higher incomes, along with increasing industrialisation, is also driving up energy demand. Nevertheless, UNECA is upbeat about the potential for positive outcomes, provided a Green Agenda is pursued. Arguing that reliable and affordable energy is central to responding to population growth, to urbanisation and to greatly improving industrialisation, their Green Agenda predicts a drop in energy production costs of 5% per year between 2015 and 2050, while seeing generation of per capita capacity increasing by 400%, investment in hydropower by 300% and investment in renewables by 3,000%. But achieving this Green Agenda is reliant on effective policies and incentives that attract investors. A number of African countries are currently in an energy crisis and the situation is worsening. However, crises stimulate change–the African energy crisis can be turned around into positive industrialisation, accelerating economic growth. But there is very little time– urbanisation will reach a critical threshold long before 2050. Where does Africa’s strategic advantage lie? This is the crux of the choice facing the continent. Implementing the Paris Agreement and ratcheting up ambition beyond the INDC targets is important for political solidarity and global diplomacy. Achieving goals that substantially exceed these is critical to Africa’s socio-economic development and to economic transformation. Visit www.oneworldgroup.co.za References

International collaboration at the OECD Forum 2016 OECD work on green growth and sustainable development OECD and the Sustainable Development Goals |

Belynda Petrie

|

Related Documents