|

Nigeria’s food crisis needs structural responses to restore trust and build an inclusive, resilient society throughout the country.

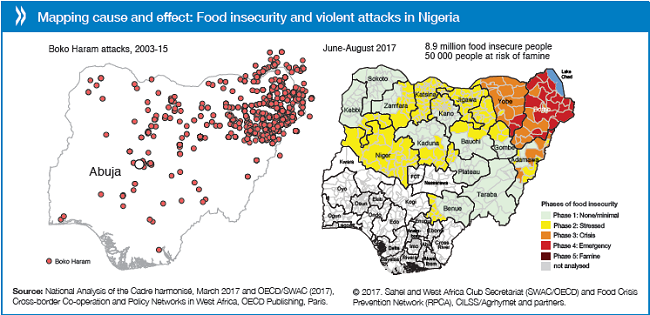

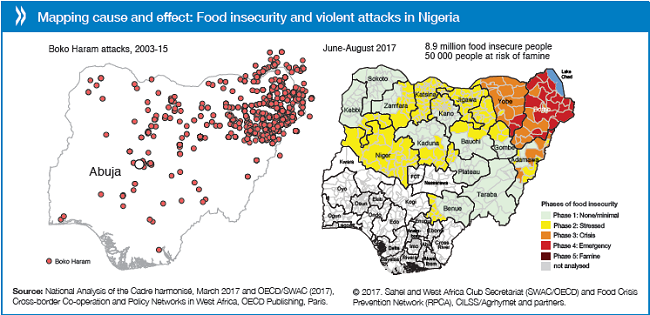

Nigeria is afflicted with famine. Of the 9.6 million people in need of food and nutrition assistance in the Sahel and West Africa (March-May 2017), some 7.1 million live in Nigeria: 3.2 million in Borno State, 800,000 in Adamawa State and 600,000 in Yobe State, and the rest in other northern states. Admittedly, this represents less than 5% of the population of Africa’s most populous country of over 180 million people, but is nevertheless an intolerably large number, nearly equal to the entire population of neighbouring Togo.

Moreover, according to our most recent data, some 44,000 more Nigerians currently face the threat of famine, mostly in Borno State. If urgent humanitarian assistance does not reach the zones that are currently inaccessible, this number is likely to rise to 50,000 people.

Eight years of violent conflict across northeastern Nigeria, caused notably by Boko Haram, an Islamic extremist group, have severely weakened the population’s already fragile livelihoods and caused a deep humanitarian crisis. The resulting massive population displacement has left the three northeastern states, Adamawa, Borno and Yobe, with extremely high levels of food insecurity. According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), 1.8 million people have been internally displaced; about 1 million houses were destroyed by Boko Haram; more than 1,200 schools are damaged and 3 million children need educational assistance. The Nigerian government indicates that some 26 million people have been affected by Boko Haram, and the Borno city of Maiduguri alone hosts more displaced people than all European countries put together. Disruption of market supplies, destruction of infrastructure and soaring food prices have severely limited access to food.

Several regional organisations and international partners have issued calls for action. However, the crisis has not gained much attention on the international stage, partly due to the hesitant reaction of the Nigerian government. For a long time, Nigerian government representatives denied the depth of the crisis, partly blaming humanitarians for exaggerating the problem or for treating Nigeria as a cash cow. The government of Nigeria officially declared a nutritional emergency in the state of Borno in June 2016 and acknowledged the need for international support. Less than a third (US$78.5 million) of the Humanitarian Response Plan for Nigeria in 2016 has been funded. The UN appeal for 2017 now aims to raise US$1 billion. In February 2017 at the Oslo Humanitarian Conference on Nigeria and the Lake Chad area, donors from 14 countries (mostly in Europe, but also Japan and Korea) pledged US$672 million for the next three years.

Peace in action

Today, even more than funding, protection and access to Boko Haram-controlled territories are key challenges. Authorities have a month to two-month window to avert a famine in the nonaccessible areas. Though a massive inflow of humanitarian assistance has improved the situation in many parts of Adamawa and Yobe, it is expected to deteriorate again during the coming lean season from June to August 2017. As long as Boko Haram continues to devastate the Lake Chad area, Nigeria and its neighbours will find themselves in a similar situation each year.

Beyond the immediate humanitarian emergency, the Nigerian crisis requires three long-term response strategies:

First, focus on bringing peace and security to the Lake Chad area. The fight against food and nutrition insecurity in northeastern Nigeria cannot be won without driving back, if not defeating, Boko Haram. A comparison between the map of food insecurity and the map of Boko Haram-related violence illustrates just how closely civil insecurity and food insecurity are intertwined.

There are encouraging signs that security forces such as the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) have started co-ordinating their actions more efficiently. Since his election in March 2015, President Buhari has made the fight against Boko Haram a top priority. Several prominent Boko Haram leaders have been arrested or killed; civilian authorities have progressively regained access to Boko Haram-controlled areas; and most recently, in early May 2017, 82 of the 276 Chibok schoolgirls captured three years ago were released. But, aside from purely military solutions, lasting peace requires restoring local governments and building trust and resilience among the local population. It is a collective effort that should involve all parts of society.

Secondly, think long-term and across borders. In December 2016, the Food Crisis Prevention Network (RPCA), with the support of the Sahel and West Africa Club Secretariat (SWAC/ OECD), urged international partners to shift from emergency assistance to long-term reconstruction and development of the Lake Chad region. One starting point would be to align the priorities of development partners with President Buhari’s North-East Initiative and the government’s economic development strategies. These aim at “gradually shifting the focus to reconstruction, resettlement of Internally-Displaced Persons (IDPs) and support for the re-establishment of livelihoods.” Because of its cross-border nature (impacting Cameroon, Chad and Niger), this initiative demands regionally co-ordinated collective action. So far, response plans are focused solely on individual countries. This is hampered by competition over financial resources between countries and partners alike. The countries of the region and their partners must co-operate more effectively at the regional level.

Thirdly, restore trust and invest time and effort into building inclusive, resilient societies. Local people, rightfully, expect their leaders to deliver basic social services including education, health services, access to water, electricity and other infrastructure. Populations in the far northeast of Nigeria have long been overlooked by public policies, with widespread hostility and a loss of trust in government being essential problems. Regaining public trust is a major task but is of paramount importance and could take years, if not decades, to achieve.

Clearly, the Nigerian crisis reflects the importance of inclusion. For a long time, the food and nutrition crisis in the northeast of the country was largely ignored by the south, and Boko Haram was seen as a “northern” problem. It was only when suicide bombings hit the major cities and the capital Abuja that the country as a whole woke up to the threat Boko Haram posed. The idea of Nigeria as “one people, one nation” has marked the country’s history since independence over 50 years ago. Its effects beyond Nigeria cannot be understated: as a senior US official, Nathan Holt, put it: “the future of Nigeria matters not just for Nigeria, but very much for its neighbours and […] for this planet.” (Africa: Briefing on Nigeria, by Nathan Holt, Deputy Director, Office of West African Affairs, Bureau of African Affairs, May 2017).

What started as a localised Nigerian crisis may quickly grow into one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises. It is a danger that Africa and the world cannot afford.

Visit www.oecd.org/swac

Bossard, Laurent (2017), “Borders and Networks: The Forgotten Elements of Development”, on www.oecdinsights.org, 17 January

OECD Forum 2017 issues

©OECD Yearbook 2017. See www.oecd.org/forum/oecdyearbook

|

Laurent Bossard

Director, OECD Sahel and West Africa Club (SWAC)

© OECD Yearbook

2017

|